If you want to invest in transportation companies, it’s important to have a firm understanding of intermodal. Retail banks? Net interest margin. High growth companies? You must understand how the market discounts future earnings and cash flows back to the present, especially in an inflationary environment.

Each of these examples are nuance. If you’re an income investor bent on utilities and packaged food companies, you don’t have to know any of these things.

But if you invest in any companies, regardless of sector or growth profile, you must understand risk.

Below are a two lenses through which to contemplate risk and what risk means for your investing practice.

Risk = Loss of Capital

Let’s say that this morning the <org> reported a jump in the Consumer Price Index, a measure for the cost of typical household items. The market will likely respond with a sell-off touting inflation concerns. The market is pricing in the risk that higher future prices will hamper future economic activity. Stock market drops.

If you and I understand “risk” as “any bad news that might make stock prices drop,” then we would do well to sell along with everyone else. But if we think of risk as the permanent loss of our investment capital, then most news-related drops become either a buying opportunity or an occasion to sit on our hands.

Over the last century of investing, this strategy alone has garnered incalculable returns.

Risk = Ability to remain a functioning adult

Investing is for anyone, but it’s harder on those that perpetually worry or doubt themselves. While financial independence in the future is a worthwhile goal, mental stability in the present is also pretty important.

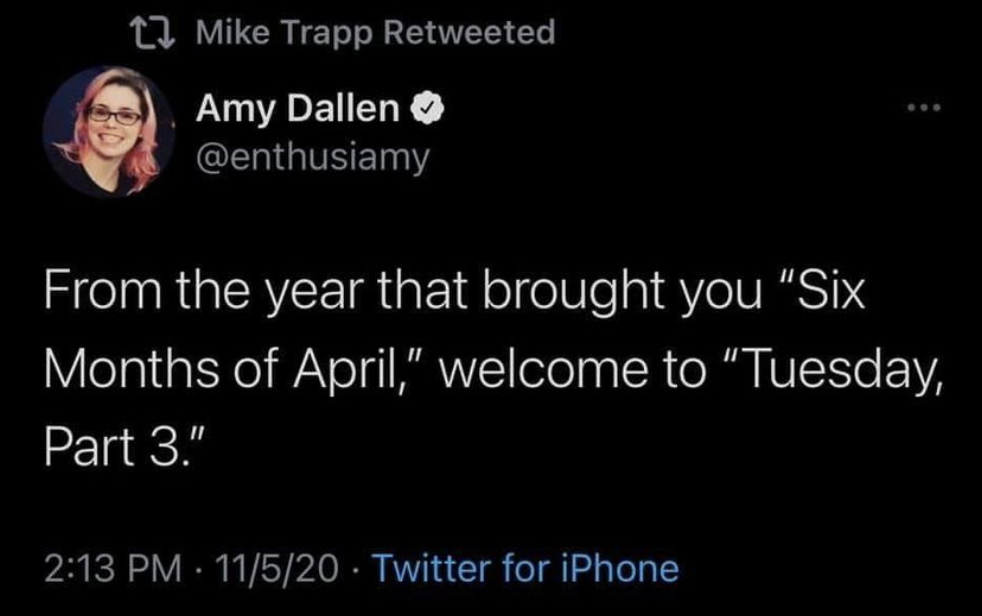

The graph above is the secret scrawling of your psyche if you cannot identify risk as anything other than permanent loss of capital. No judgment here. Just an acknowledgment that viewing volatility as risk will force investors into the calculus of “how long can I continue to feel like this and still function as a person/employee/spouse/parent, etc.?”

Fear of volatility is destabilizing, but shame can be downright crippling. Investors that let self-doubt creep in compound shame on top of fear. All light-hearted jibing aside, this can lead an investor down some very dark paths:

“I’m stupid.”

“I should have known better.

“I should have followed my gut.”

(You’re not.)

(You couldn’t have.)

(Your gut is a coward that always tells you to do two opposing things just to cover its bases.)

Permanent loss of capital or temporary loss of sanity

Whether you’re assembling a portfolio of utilities companies yielding 4% or tech stocks you expect to 4x over the next 10 years, you need to decide not just your risk tolerance, but your definition of risk itself.

The majority of my capital is in retirement accounts, so my time horizon is just under 20 years. What money I do have in taxable accounts is money I don’t need in the immediate term. For these reasons, I’m capable of taking risk and keeping my hat on, but only because:

- My main positions (about 35 companies, each representing 2-5% of my overall portfolio) are companies that I believe will not fail. While many will have swoons of 20% or more, and some will have crashes of 60% or more, they will continue to be excellent companies led by ethical, responsible management. They will continue to represent leading companies in important industries. They will continue to possess some form of competitive advantage—be that price, brand, patents, switching costs, market dominance, high barriers to entry, etc. — some advantage will keep them relevant in the market. Thus, I will never* risk permanent loss of capital.

- The remaining companies are lottery tickets. They very well may go out of business tomorrow. Their management team may be a gaggle of hoodie-wearing, Rumi-quoting narcissists with a bad gambling addiction. Their products may never clear FDA hurdles or may get eclipsed by a more competent company’s offerings. Their office building might burn down, and since Kyle didn’t take a screenshot of the design specs like I told him to, the widget they invented that would someday change the world is lost to the ages. In short, anything can go wrong.

If you pooled them together, I’d be amazed if they constituted more than 5% of my portfolio. If I were 20 years younger, that percentage might well be three times greater. But being in my mid-40’s, I need remain a functioning adult. My wife needs me, my students need me, my cat needs me. So I keep the lottery ticket weighting laughably low. As Monish Pobrai said, “Heads, I win. Tails, I don’t lose much.”

*Earlier in this post I used the word “never.” Know that “never” is a relative term. “Never” means “unlikely enough for me to worry about it. Nothing more.